▦ 4 → Infinite Space Notes

by: Shahruz Shaukat

This is a semi-technical overview of the fictional SpaceX protocol. It doesn't cover the internal post structures, just how they're framed.

Infinite addresses

Accounts in Ethereum-like systems get around the need for a centralized user database (containing usernames, emails, hashed passwords, etc) using math, cryptography, and the concept of infinity.

With Ethereum, users don't have usernames, they have addresses. All addresses are 42 characters long - starting with an 0x, then 40 hexadecimal (0-9, A-F) characters.

Example address: 0xBb167bCe93F2e1Db5aAe834702C8BDAEaB5e9831

Addresses don't have associated passwords, they have private keys instead. Private keys are 64 hexadecimal characters.

Example private key: 7704a2cb5a372c2bef0de7ccf3c7557e144affb3d276334aa2783560d0fab024

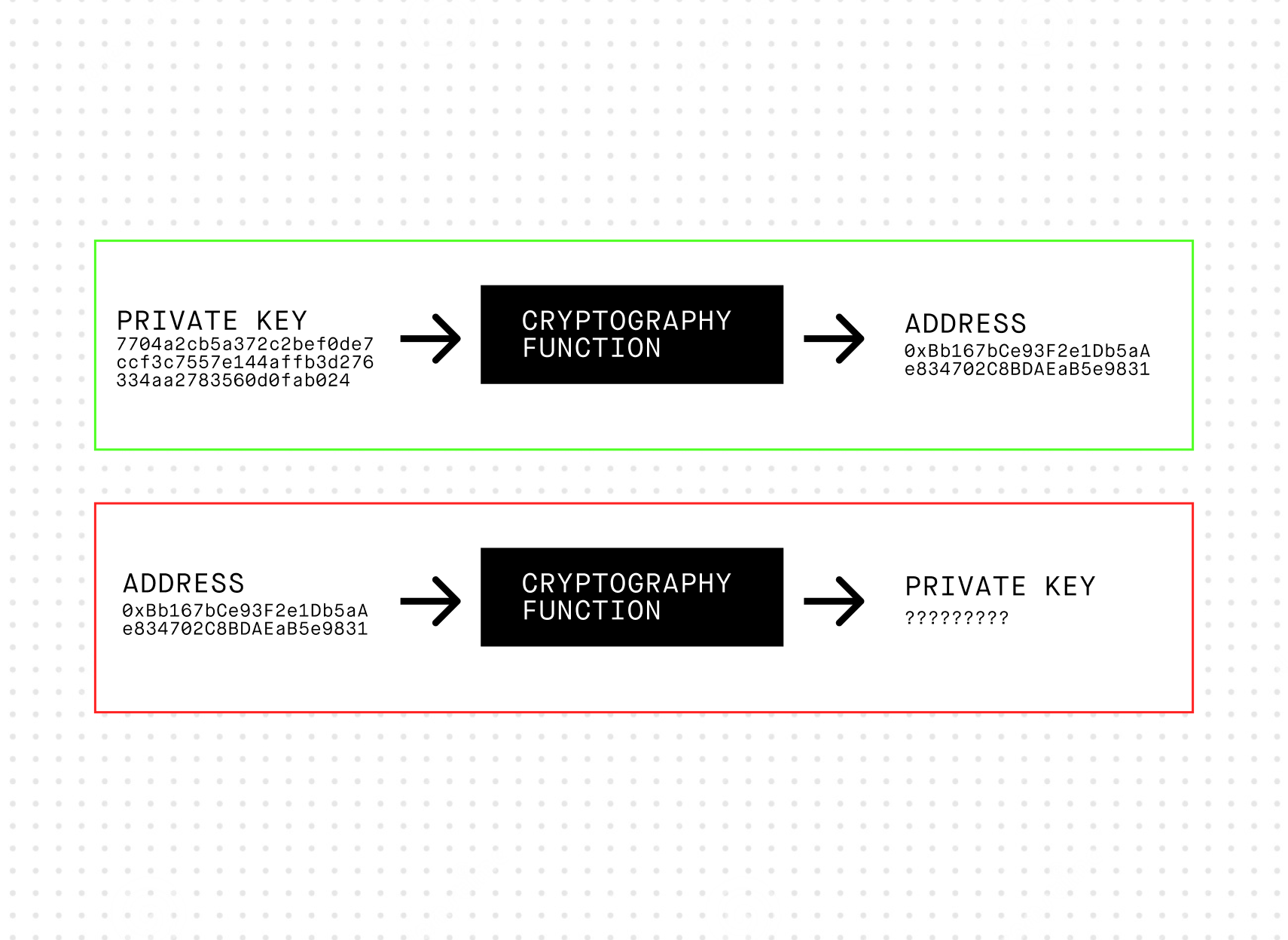

Private keys and addresses are related through a one-way function.

You can enter a private key into the function and get an associated address in response in under a millisecond.

Going the other way isn't possible. The only way to get a private key for an address is by having computers try to guess the key, which would take billions of years for the most powerful computers we have today working together to find one key.

There are 2 ^ 160 possible Ethereum addresses.

That's 1,461,501,637,330,902,918,203,684,832,716,283,019,655,932,542,976. I'm going to use "infinity" as shorthand for that number for the rest of this post because they're close enough for this context.

When you generate an Ethereum account using a wallet app (like MetaMask or Rainbow.me), the app is merely generating a random private key of 64 hexadecimal characters and getting the public address for it. Then it shows you that information, stores what it needs to store, and that's it.

It's all happening offline, there's no process of registering the account anywhere or checking to see if it's already being used.

The mathematical bet here is that people could be generating tens, hundreds, millions of addresses this way without ever running into the same private key as someone else.

Finite space

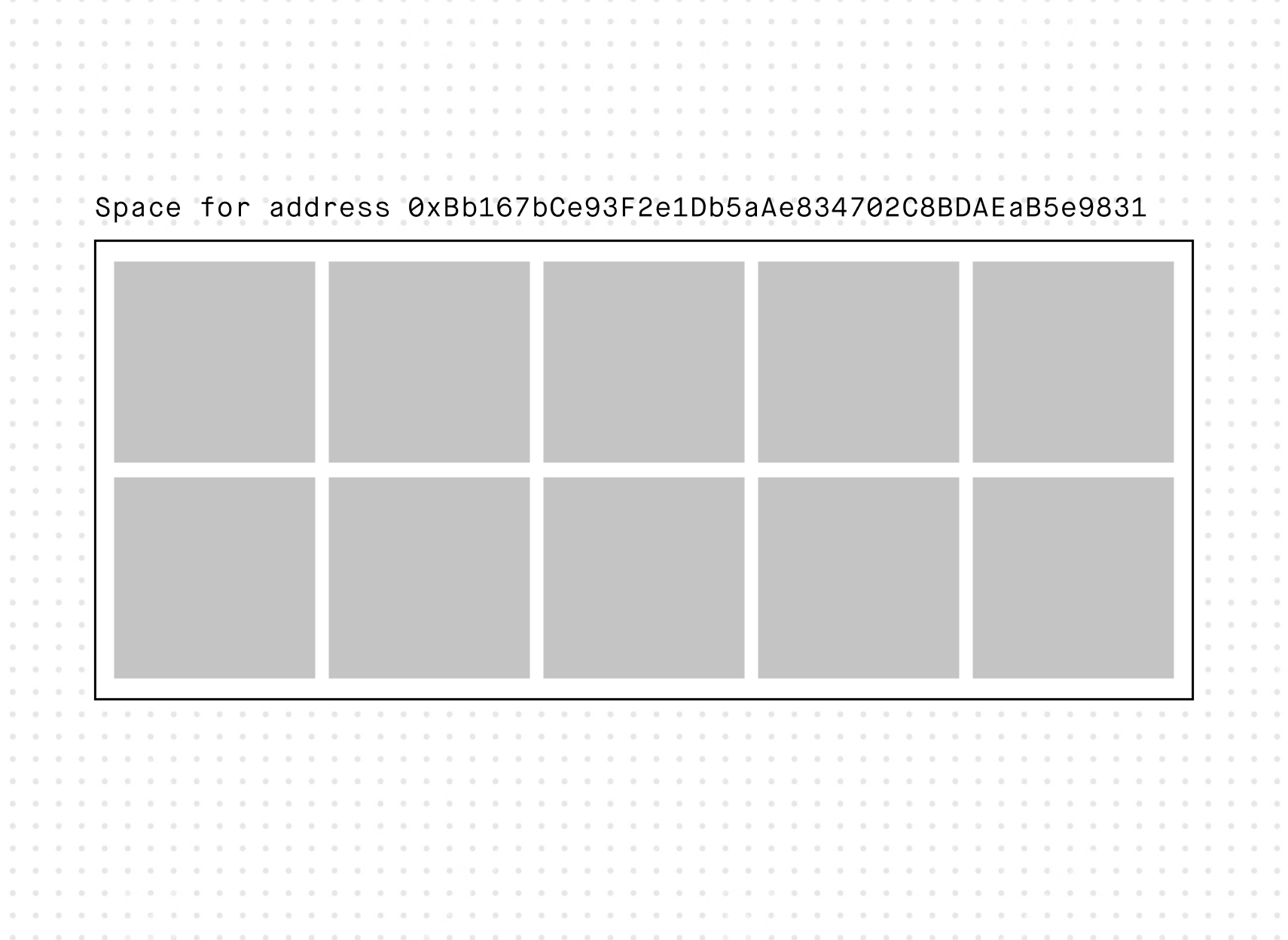

On SpaceX, each address has a corresponding "space" with 10 blocks. The geometry adjusts depending on the screen size, but everyone starts with 10 empty gray squares, and they can fill them in and move them around however they'd like. Each post contains a bit of metadata to customize the block its in - background colors or images can be set, they can play sounds when you hover over them, and so on.

SpaceX Folk Culture

Unlike the conventions of our own world, there's no sense of chronology or time on SpaceX.

More importance is given to the notion of space. Users can only ever have 10 posts up at a time in any address's space, so they curate their own carefully, and spend time considering the layout of other's spaces when browsing them.

Initially, SpaceX was a "single-player" protocol to be used like a notes app. Users interested in sharing publicly could set up a space with the same personal address they use everwhere else. For private notes, they'd just generate a brand new address and start using it in SpaceX. They'd set up addresses for small personal things like shopping lists, or big public things like debating policies for the governments in their meatspace.

Eventually, SpaceX users invented their own version of the "reblog". The trick was simple: just copy-paste the contents of a post somewhere else into a block in your own space.

Because all the posts were stored on IPFS (where duplicated content always lives at the same URL), SpaceX clients would unintentionally show the original author's metadata in the right place, instead of the space owners' who had copy-pasted it in.

This ended up being a thing a lot of people liked, so clients quickly added in an "Import" button to make this easier to do.

Patterns like this kept emerging over time: people would bump into interesting quirks in the SpaceX protocol, find ways to make them useful for themselves somehow, then others would discover these and start trying it themselves, and eventually expect their client apps to make those new things easy to do and feel less like a hack.

The apps found it hard to keep up: most had found sustainability and a level of peacefulness by creating SpaceX clients targeting specific interests or uses.

But suddenly a big part of every client's users wanted things to change one way, and another big part would want things to change the opposite way, and another part never wanted anything changed except for maybe a new rule to saying no more changes after this one.

Post 10 covers a Governance technique that emerged from this situation on SpaceX.

🕊 Where to next?

▦ 6 → Interplanetary Filesystems

✸ Tabs roll call